Find more on Suzanne Paddock at www.suzannevpaddock.com

Find more on Padraig O Tuama at www.padraigotuama.com

Find more information about Kathy Keler at www.kathykeler.com

Find more on Mary Grace Thul at sistermarygrace.artspan.com/

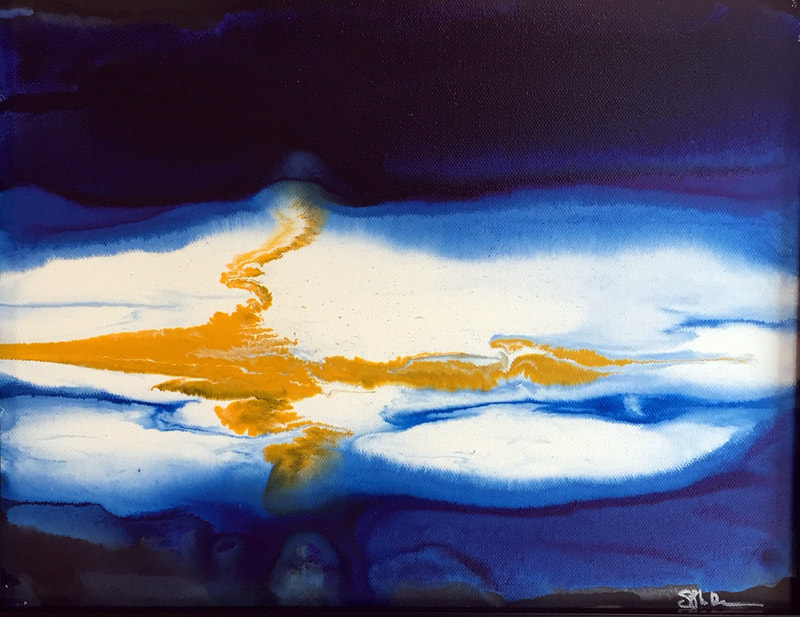

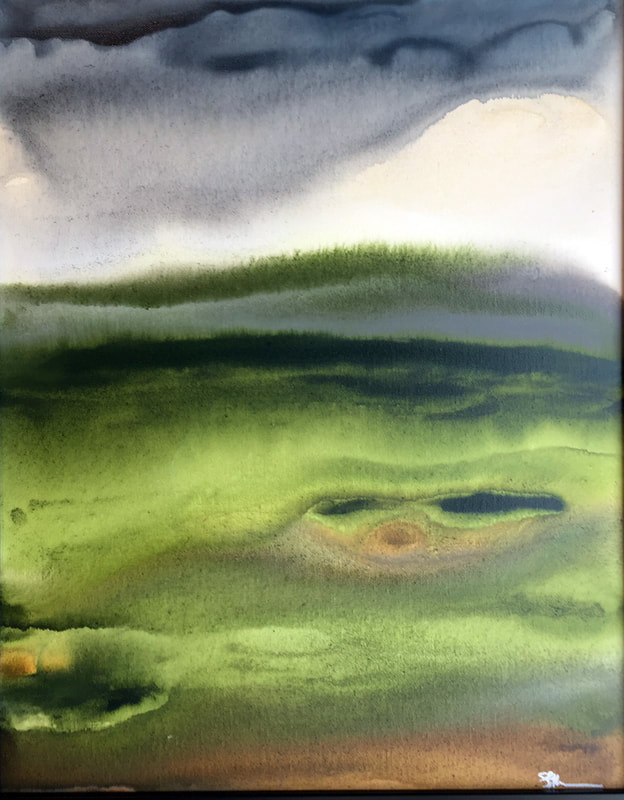

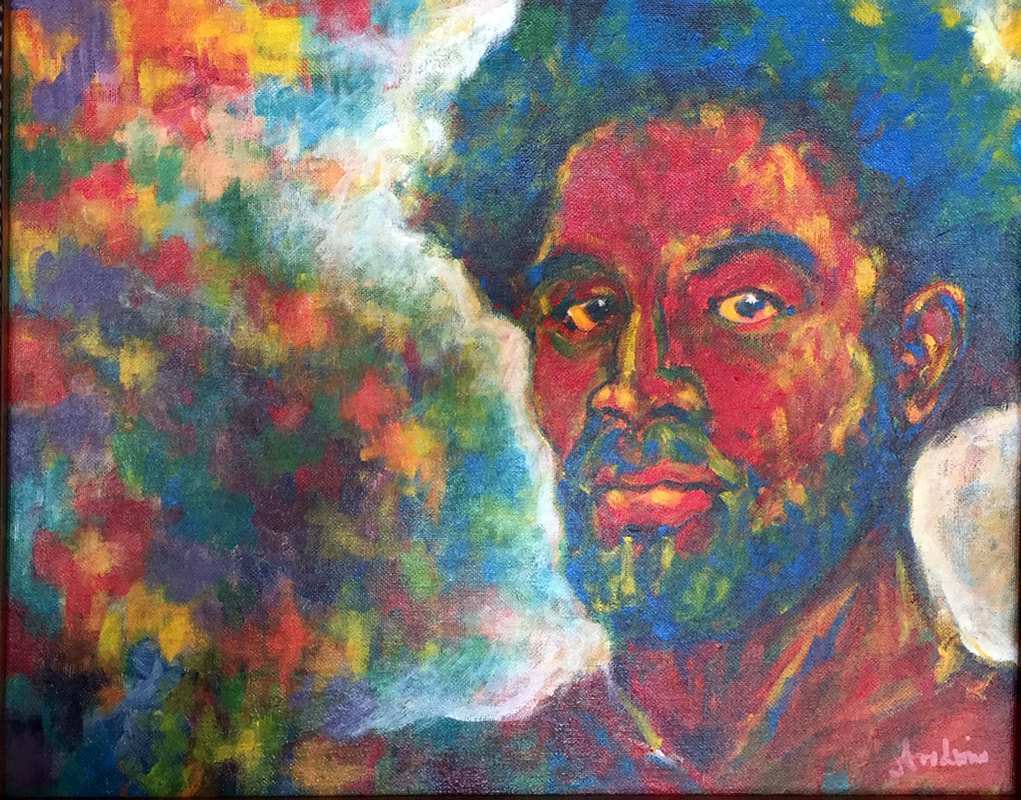

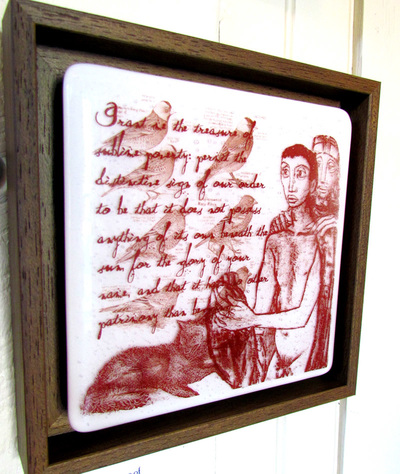

One of the most haunting verses of devotional poetry I ever encountered was in Hans Urs von Balthasar’s The Way of the Cross. In the final station, Jesus’ corpse has been taken down from the cross, the body is swathed according to custom, and laid in a tomb … and von Balthasar suggests that a great and festive liturgy of forgetting begins. So already his unquiet image haunts heads and hearts. Already the spirit is freed. Already the Easter question takes shape … But silently. For tomorrow is only Holy Saturday. The day when God is dead, and the Church holds her breath. That strange day that separates life and death in order to join them in a marriage beyond all human thought. We wait for justice a lot! It seems to us that we hold our breath many more days of the year than this one solemn and holy-Saturday. Our world seems to endlessly churn out events in which we question the existence of a god or we feel ensnared or helpless or lost. Portiuncula Guild offers the following images and prayers as a rumination for the coming days. These four images were created by profoundly insightful local artists. We bring together as a tiny Triduum exhibition. Our simple aim is to juxtapose these images with the prayer of the church and give us an opportunity to think about the causes, situational factors, and consequences of so many negative emotional experiences that surround us at this moment. During these holiest of days … art and prayer and politics collide in narratives of the passion, death and resurrection. Tyrants and priests, apostles and unbelievers, history and current events, faithfulness and betrayal, partisans and zealots all become characters or themes in a great cosmic drama set within a regional struggle for political power, religious belief and economic control. If the Easter question can take shape amid that narrative … maybe, just maybe we too can hold our breath … and wait … and believe that in our current situation there is the possibility of resurrection and new life. Holy Thursday

Good Friday

Easter Vigil

Easter Monday

All the world’s great religions structure their liturgical year around a series of feasts, festivals, and esoteric practices that seek to express the mystery of God. Whether it’s exploring the innumerable characteristics of God or the complexity of a life of faith, these annual events enable believers to delve into the various mystery of faith … one little chunk at a time. Through the retelling of ancient stories and sacred myths believers grapple with eternal questions of creation/destruction, right/wrong, and good/evil. Each year, believers connect their current situation with their past in order to open their eyes and their hearts to live more honestly, clearly, and compassionately. These narratives have the power to lead the hearer from the unreal to the real, from the temporary to the eternal, and from the false to what is ultimately true. The four themed exhibitions this year at Goose Creek Studio focus around the Christian seasons of Lent, Easter, Pentecost and Advent and under the title L’anneé Liturgique (see endnote). For Christians, this is the season that recounts tales of slaves being freed from bondage. In these 40 days the prophet describes deserts that bloom, lions and lambs lying down together and a child playing at a cobra’s den. This is the season in which the dead are said to be raised, and Christians proclaim that death has no power. These are 40 days about imagining the impossible … a world once again restored to what God created it to be. We see this belief in the impossible in the sensitive pencil portraits of famous Americans by Robert Pennix. The artist portrays men and women that made a difference and changed our world for the better. Pennix also gives a loving nod to an emerging generation of prophets and visionaries that are working for a healthier future. Jean Horne’s four large acrylic painting narrate the words to Danny Schmidt’s folk ballad Stained Glass. A morality tale that suggests that even the emblazoned imperfections of human life can reflect perfect streams of light. Sara McDowell’s landscapes explore the duality light and darkness … existing simultaneously and separately … like the spiritual, social and internal journey of this season. And finally, Helen Hubler literally captures images of kids in cages at our southern border. This artist’s graphic work reminds the viewer despite this season of imagining, our world continues to be filled with suffering, bondage and death. The original intent of the show was to focus solely on these four artists and these extraordinary bodies of work. But as the show came together several works already in the gallery demanded their place. So this exhibition features several special guest appearances by other Goose Creek Studio creative partners and their work; Melanie Layne Hylton’s meticulously-burnt pyrography portrait of Mother Teresa, Lynn Goodwin’s cheeky portrait of a black Christ, and the charred pit fired works of local potter Andre Namenek add to this exhibition’s narrative of imagining the impossible. Faith is the Assurance of Things Hoped For graphite portraits Robert Pennix (See more on Robert Pennix in Lynchburg Living Magazine) By faith the people passed through the Red Sea as if it were dry land, but when the Egyptians attempted to do so they were drowned. By faith the walls of Jericho fell after they had been encircled for seven days. By faith Rahab the prostitute did not perish with those who were disobedient, because she had received the spies in peace. And what more should I say? For time would fail me to tell of Gideon, Barak, Samson, Jephthah, of David and Samuel and the prophets who through faith conquered kingdoms, administered justice, obtained promises, shut the mouths of lions, quenched raging fire, escaped the edge of the sword, won strength out of weakness, became mighty in war, put foreign armies to flight. Women received their dead by resurrection. Others were tortured, refusing to accept release, in order to obtain a better resurrection. Others suffered mocking and flogging, and even chains and imprisonment. They were stoned to death, they were sawn in two, they were killed by the sword; they went about in skins of sheep and goats, destitute, persecuted, tormented of whom the world was not worthy. They wandered in deserts and mountains, and in caves and holes in the ground. Yet all these, though they were commended for their faith, did not receive what was promised, since God had provided something better so that they would not, apart from us, be made perfect. Letter to the Hebrews, Chapter 11 Stained Glass acrylic on canvas Jean Horne (inspired by the lyrics of "Stained Glass" by Danny Schmidt) Duality mixed media Sara McDowell

Confiteor oil on canvas Helen Hubler

* ENDNOTE: As you know by now, Goose Creek Studio and the Portiuncula Guild are making a more intentional effort to explore faith, creative expression and the spirituality of the art making process as we move into our second decade. The guiding theme of our in-house gallery exhibitions this year is L’annee Liturgique (the liturgical year). This term comes from a title of work by the French Benedictine Abbot of Solesmes Abbey Louis Guéranger. Ok, maybe a rather obscure and esoteric reference! But two key elements of Dom Guéranger life and work were the re-establishment monastic life in France after it had been wiped out by the French Revolution and reconnecting the scriptures to the pastoral care and the liturgical life of his congregation.

The core of Dom Prosper Guéranger’s work was the question of how to better assist his congregation cope with a rapidly changing (and often violent) world around them. He recognized that humanity (and the world) were in great flux and that the weekly church service too often failed to provide the inspiration, comfort or direction that his flock needed to navigate changing times. Guéranger was convinced that one key to the church becoming relevant for his parishioners again was the opening-up of the key biblical stories told throughout the liturgical year. He believed that the core values and moral lesson embodied in scared stories could enable folks cope with a fast-changing world. Interestingly, Guéranger’s work was the foundation for not only 20th century church renewal, but also the basis for many artists contributing new works of art to the re-building thousands of destroyed church after the two world wars in Europe. Many of the artistic masterpieces of the 20th century, from artists like Picasso, Leger, Chagall and Le Corbusier, can be traced to this pastoral movement to make sacred stories relevant in the lives of contemporary people. Four of our gallery exhibitions this year will be focused on the liturgical seasons of Lent, Easter, Pentecost and Advent. In addition to the regular 2nd Friday receptions that fall within the dates for each show, we will also be hosting a more intimate prayer, reflection and artist talk at the opening of each liturgical season. Here are the dates and time … 40 Days: 4 Small Exhibitions by Robert Pennix, Helen Hubler, Sara McDowell, and Jean Horne Wednesday, February 26, 5:30 PM Signs and Shibboleths: (Guest Curated by Janet Chalker) with art by Ally Turner, Dotti Stone, Caroline Renard, Patty Malanga, Nancy Laurent, Shelley Koopman, Sharon Kessler, Dick Hendrix, Revelle Hamilton, Donna Gallucci, Patrick Ellis, Pat Dougherty, Janet Chalker, Mitchell Bond, Linda Black, and Des Black Saturday, April 11, 5:30 PM Connections: Photographs by Jean Wibbens Sunday, May 31, 5:30 PM Shadow Boxing: A Creative Partners Group Show (details to come) Sunday, November 29, 5:30 PM

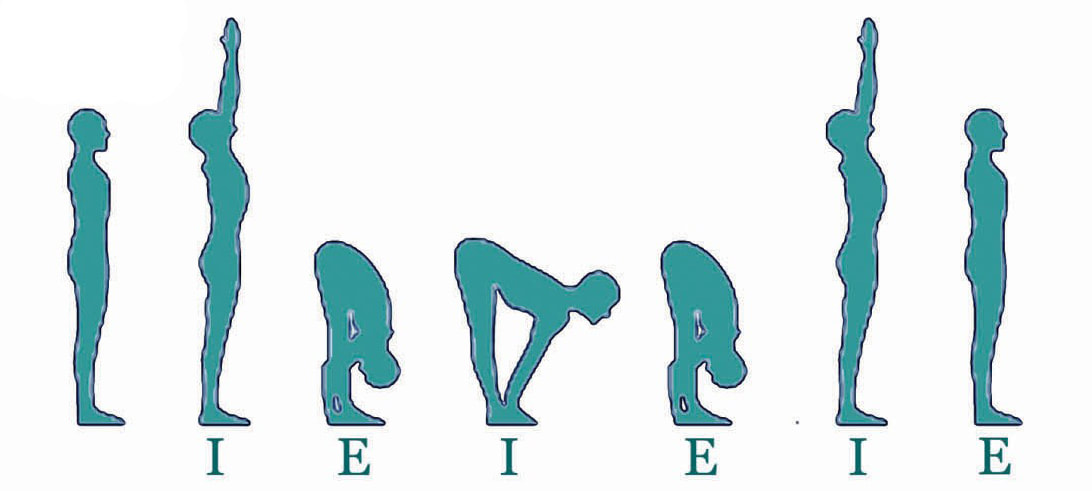

The writer of the Book of Daniel often begins his moral or ethical folktales with a historical marker situating the story in actual human history; “in the first year of the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon,” “in the second year of the reign of Cyrus, King of Persia.” These tales of human courage and faithfulness are set within the clash between the human will for the survival and the human will for self-destruction. In each story, the interplay between the reigning tyrant and a faithful hero sets-up the narrative’s plot and ultimately the tale’s moral and ethical lesson. Both Chapter 6 and Chapter 11 begin with the historical marker “in the first year of the reign of King Darius the Mede.” This installation draws on elements from these two chapters – a song in Chapter 6 after Daniel’s trial and deliverance from the lion’s den, and the sweeping 250-year overview of human history found in Chapter 11. The world history outlined in Chapter 11 presents a sweeping drama of armies and kings at war in all corners of the ancient middle east. A tapestry of blood, anger, greed and self-serving tyrants from the Babylonian Empire, through Egyptian, Persian and Macedonian conquest, all finally culminating in Syrian control under the rule Antiochus IV Epiphanes. A real-life biblical Game of Thrones describing two and a half centuries of human vanity, greed and sinfulness that brings about an ongoing legacy of death and destruction. Hovering over this global chessboard are the words to a song voicing the central message in the Book of Daniel. This liturgical canticle in Chapter 6, remarkably, does not come from Daniel but rather comes from the mouth of King Darius after Daniel’s miraculous deliverance from certain death. The words to this song give the reader an alternative way of thinking about life together in this world, as well as the certainty that God will win in the end over the destructive powers of oppression and violence. Ultimately the events of history are not ordained by God but are rather the result of free human choices centered in greed and selfishness … humanity’s ever-present sin of desiring more than it needs at the expense of its neighbor’s life and livelihood. The various folktales of the Book of Daniel were brought together at one of the lowest points in Jewish religious and cultural history. The stories served to give direction and hope to a people of faith caught in the middle of extreme cruelty and oppression. The writer weaves together a rich sampling of hope-filled Jewish stories during a time when religious practices were outlawed, Torah scrolls were being burned, children were torn from their mothers, and the temple was being desecrated with images of foreign gods and the sacrifice of unclean animals. The writer gathers stories of faithfulness and interweaves them with the various kingdoms from human history to remind the faithful that the struggle for survival in the time of tyrants is not new. This is an ongoing struggle within the history of all people seeking to live in covenant with their god and neighbor but find themselves caught up in some seemingly beyond their control. While the stories highlight the interplay between a faithful hero and the powerful (and often witless) tyrant, the target audience of the writer’s work are the simple people of faith who need a road map for what to do next and how to respond to evil in their midst. Interestingly, many other unsavory characters emerge in the storytelling. The legions of sycophants who surround the king and his court plot and manipulate in order to gain favor, protection and prestige from the tyrant. Likewise, a host of compliant religious leaders who choose to ally with the king for many of the same reasons. For the writer of Daniel, the tyrant, the sycophant, and the compliant religious leaders put their faith in people or powers or systems that ultimately cannot save. But maybe more interesting, the writer also calls the simple religious folks to accountability. In a lengthy prayer after his deliverance from the Lion’s den, Daniel first recounts how God has delivered his people in the past and describes a God whose steadfast love is both renowned and dependable. But then Daniel’s words become penitential and he declares that the faithful have also sinned and done wrong, been wicked, and rebelled. They too had forgotten how to live in right relationship with god, with each other, and with their world. The path to wholeness begins with their own confession. Over the past three centuries, the folktales of the Book of Daniel have had an honored place in the shared canon of both Jewish and Christian revelation and imagination because humanity has too often found itself in this same pattern of death and destruction. Today, many of us find ourselves needing a roadmap for responding to evil in our midst and a world dangerously out of control. We too live in a world of saber-rattling madmen surrounded by cheering sycophants, evangelical religious leaders that equate their own economic security with god’s blessing, global economic systems that are enthusiastically endorsed but benefit the very few, extreme nationalism disguising itself as patriotism, and an intentional policies of inhospitality directed at those most vulnerable and needy among us. The community that Daniel was writing for two and a half centuries ago would have understood our dilemma and responded … God will triumph.  Sacrifice. Often when we talk about war or conflict, we speak in terms of sacrifice. The soldiers, the families and the communities who sacrificed life, relationship and treasure in pursuit of a “greater good” become the currency a nation spends. When the sacrifice becomes too big, the cost too high to imagine it can become blurry and impossible to comprehend. Individuals, like the soldiers from Bedford, become surrogates for the millions that died in battle. They become the lens we use to humanize the horror, to grieve and feel gratitude without being immobilized or hardened by the facts. Their sacrifice gives us a path to consider all that was done and all that was lost. On June 6, 1944, 35 men from Bedford came to Omaha beach to take Europe back from Nazi Germany. Nineteen of them did not survive the day. Those 19 men were part of 842 men who died on Omaha Beach who were part of the approximately 10,000 soldiers that died on D-day. The 77-day long battle for Normandy was brutal with a casualty rate of 6,675 people a day. By the end of WWII approximately 4,000 Bedford county citizens, out of a population of 40,000, were in uniform. Somewhere between 70 – 85 million people died in WWII, approximately 3% of the world’s population, many from war related disease and famine. This piece honors the story of the men from Bedford specifically, but also pays tribute to those who have fought and sacrificed on foreign soil and at home. Hopefully, it also speaks to what can come from sacrifice - what can grow in the fields of despair or blossom into better being. In Flanders Field by John McCrae In Flanders fields the poppies blow Between the crosses, row on row, That mark our place; and in the sky The larks, still bravely singing, fly Scarce heard amid the guns below. We are the Dead. Short days ago We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, Loved and were loved, and now we lie In Flanders fields. Take up our quarrel with the foe: To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields.* *emphasis added Note – Flanders field is located in the county of Flanders in southern Belgium and north west France which was part of the western front during WW I. This poem was written by a Canadian doctor Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, inspired by the poppies growing amongst the graves of those who had died on the battle field. Poppies were also chosen to honor my Grandfather, George Gill, who fought in WWI and will be forever remembered handing out poppies in support of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW).  The Bedford Boys fought for freedom so that I can now fight for equality and justice for all. “So much is lost when we refuse to cross the “borders” that keep us apart. How much are the people for whom Christ died suffering because we remain paralyzed and divided by our differences when we should be working together as the hands and feet of Jesus in the world? There must be a better and more efficient way to carry out our roles within the mission of God. Surely, we can do better.” Christina Cleveland, Disunity in Christ: Uncovering the Hidden Forces That Keep Us Apart. (InterVarsity Press, 2013) Watch and Wait...for Change My heart shall sing of the day you bring. Let the fires of your justice burn. Wipe away all tears, for the dawn draws near, and the world is about to turn. from “The Canticle of the Turning” - a contemporary setting of the Magnificat During the season of Advent, we watch and wait for a turning world – one characterized by justice, comfort, a new dawn. This new order is also characterized by seemingly incomprehensible reversals – the lion and the lamb lie together, the first will be last and the last will be first, a little child will lead them. Change is constant and inevitable. It can be exciting and longed for, but it can also be upsetting and uncomfortable. Through the practice of yoga – on and off the mat – we build skills to manage the ups and downs of change in our lives and the world. Through observing change without judgement or attachment, we can cultivate gratitude, balance, and joy. What change are you longing for? What change do you fear? How do you watch and wait for change in your life and in the world? Pose Savasana is customarily the final pose in an asana practice. It involves lying in complete stillness in order to integrate the effects of the practice. Total relaxation is the goal of savasana and, for that reason, it is often called the most difficult yoga pose because our minds are going in a thousand different directions and our bodies are tense and fidgeting. Some may shy away from using the English name for savasasa – corpse pose. Thinking about one’s self as a corpse might be thought of as morose and unappealing. However, an asana practice can be considered a metaphor for a day, a season, or a lifetime. Finding ease in our “corpseness” in savasana, we in some sense prepare for ease in the many deaths experienced throughout our lives. Savasana becomes the concluding and a beginning act – a death to one’s old self and a rebirth to a new creation. Here are some links to more thoughts about corpse pose: Watch + Learn: Corpse Pose, narrated by Jason Crandell, yogajournal.com The Subtle Struggle of Savasana, Nikki Costello, yogajournal.com Breathe Use your breath to change your body. Read more about it: Yogic Breathing: The Physiology of Pranayama, Kripalu Center, huffpost.com Breathing for Life: The Mind-Body Healing Benefits of Pranayama, Sheila Patel, M.D., chopra.com Practice Consider creating a visual focus in your practice space. This may be as simple as finding a favorite piece of art or a special object to place in a central location. Or it could be creating a home altar with religious icons and texts, incense, photos of ancestors, and natural objects such as stone, leaves, or plants. Such tangible visual references can provide a focal point during practice. They can also remind you of your intentions as you pass by them in daily life. MEB

Watch and Wait...for Joy

Is there a difference between pleasure and happiness? Dr. Robert Lustig argues that there is and that our inability to recognize the difference is killing us. Lustig’s research focuses on the biological roots of pleasure and happiness. It comes down to the balancing of two neurotransmitters – dopamine (which regulates pleasure) and serotonin (which regulates happiness). An excess of dopamine leads to addiction and a decrease in serotonin leads to depression. So, contrary to how we are often wired, we need to seek out strategies that tamp down dopamine production (pleasure) and increase serotonin production (happiness). Lustig suggests the following strategies, which he calls “The 4 Cs”: 1) Connect – In-person, face-to-face time with other people, 2) Contribute – Do something that makes the world a better place, 3) Cope – Focus on sleep, mindfulness and exercise, and 4) Cook – Eat real, whole foods. For much more detail on these ideas, see the following (the first two provide a simple overview and the last is more in depth): The Difference Between Happiness and Pleasure and Why It Matters at Work, Gabriel Kauper, deliveringhappiness.com How to Solve for Chronic Unhappiness: The Four Cs, Gabriel Kauper, deliveringhappiness.com Are Big Corporations Hacking the American Mind, an interview Robert Lustig on The People’s Pharmacy, peoplespharmacy.com

Breathe

Square Breathing is a practice of observing inhales and exhales along with the pauses in between. Find a comfortable seat. Close your eyes or lower your gaze. Breathing through your nose, inhale to a steady count of 4. Hold the inhale for a count of 4. Exhale for a count of 4. Hold the exhale for a count of 4. Complete 3-5 full squares.

Practice

Using music to create pleasing sensory experience on the mat can help in sustaining your practice over time. Just as you choose movement and breathing which lead you to be more focused, relaxed, and in the present moment, the music you choose should be an aid to your practice and not be a distraction. There’s no right or wrong music to use. However, if you choose music with lyrics, carefully consider songs with words that contribute to your well-being. Take some time to explore music apps to find new music. Here are links to a couple of Youtube playlists I’ve compiled – one instrumental and one vocal:

MEB

Watch and Wait...for Balance

“Every valley shall be lifted up, and every mountain and hill be made low; the uneven ground shall become level, and the rough places a plain.” Advent heralds the coming of a new beginning, a new world order characterized by an upended status quo – an evening out, a leveling, a balancing. In anticipation of this time, we watch, we wait, we hope, we prepare. On the mat, we explore balance through movement and mindful breathing. By intentionally practicing physical balance (and imbalance), we watch/wait/hope/prepare for a deeper balance in our lives and in the world. What brings you balance? How do you manage imbalance? What are your roadblocks to finding balance? How do you apply lessons learned from balancing on the mat to life off the mat? Pose While practicing the balance pose Vrksasana or Tree Pose, yoga teacher J. Brown suggests “being prepared to fall out with a smile on your face.” This cue is a reminder to be content regardless of whether or not you “stick” the pose. The imbalanced parts of poses are just as important, if not more important, than the balanced parts. Wobbling and falling out of balance poses are not mistakes. Rather they are a critical part of the practice. Learning to be content (smiling, breathing, non-judging) with imbalance on the mat, can develop equanimity which is transferable off the mat. So that you can approach times of imbalance in life with the same smiling, breathing and non-judging contentment. Here are some links to balancing practices you may want to try: Three Versions of Tree Pose, Baxter Bell, youtube.com It’s All About Balance, Dianne Bondy, youtube.com Finding Your Balance Off the Mat, Dianne Bondy, yogainternational.com e·qua·nim·i·ty /ˌekwəˈnimədē/ noun: mental calmness, composure, and evenness of temper, especially in a difficult situation. Breathe Victorious Breath aka Ujjayi Pranayama is the simplest of breathing techniques to balance the breath. It involves taking deep inhales and slow exhales on an even count. As the breath passes in and out of the nostrils through a slightly constricted throat, it makes a soothing, ocean wave sound. Ujjayi can be used as part of meditation, in concert with yoga poses, or any time you need to calm yourself. Find more instruction on Ujjayi Pranayama here: Learn the Ujjayi Breath, an Ancient Yogic Breathing Technique, Melissa Eisler, chopra.com Practice You can make your home practice something you look forward to by creating a unique and special environment in which to practice. In addition to having a dedicated spot to practice, this can be achieved by paying attention to the sensory aspects of your practice area. In particular, aroma can be helpful to get you more focused on your practice. You may want to start with a pre-mixed aromatherapy room spray (available locally at Health Nut Nutrition in Wyndhurst). Once you figure out what scents you like best, you can try mixing your own essential oil combinations. Here are a couple of links with guidance for using essential oils: What You Need to Know about Essential Oils, Laine Bergeson Becco, experiencelife.com How to Use Aromatherapy in Your Yoga Practice, Julie Gondzar, doyouyoga.com 10 Homemade Air Freshener Recipes, Jill Winger, theprairiehomestead.com MEB The themes of watchfulness, waiting, anticipation, and expectation are central to the season of Advent and contemplative practices (prayer, meditation, fasting, mindfulness, yoga, etc.) are helpful tools to root one's self in these themes. Rather than focusing on doing , these practices emphasize being - stilling the mind and body to allow gratitude, balance, joy, and change to come. I am offering Watch and Wait, a four week yoga practice series at Bower Center for the Arts (Wednesdays, November 28, December 5, 12, and 19, 5:45-7:00 pm) Connecting deliberate movement and breath, this gentle restorative flow is a time to honor the change of seasons outside and in. Each practice is a combination of movement, rest, and guided relaxation. Each week will also include resources for your home practice – readings, pose suggestions, meditation and journal prompts. I will be posting these materials here for easy access.

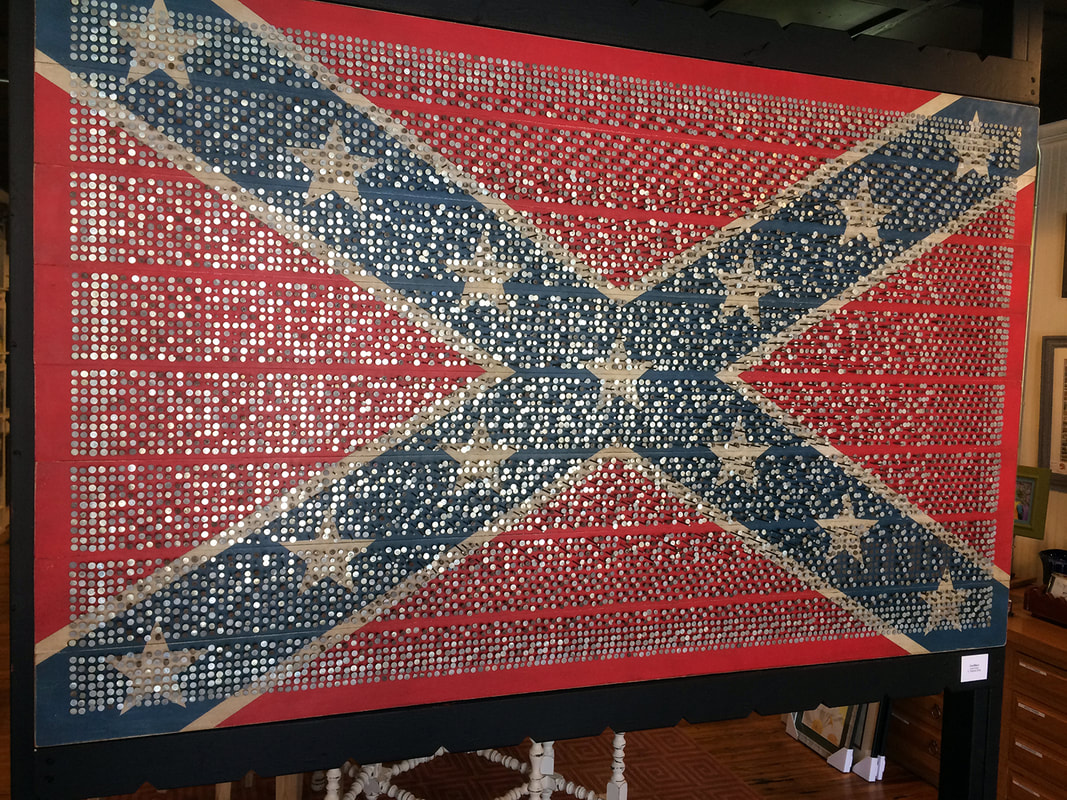

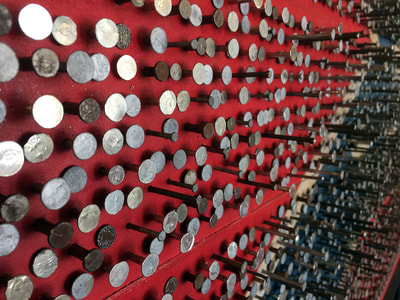

Here's week 1: Watch and Wait...for Gratitude On his “10% Happier” podcast, ABC correspondent Dan Harris interviews author and speaker Shawn Achor about gratitude. Achor, who studies positive psychology, discusses the effects of gratitude on the human body and gives ideas on how become more grateful. He says that, much as we build strength in muscles by using them over time, gratitude builds when you practice it regularly. One idea he shares is to take a few minutes each day and think of 3 new things you are grateful for. Write them down. Use them as a focus for your meditation and/or yoga practice. In time, you will have a long list of blessings. Listen to the entire interview here. Pose “Find a comfortable seat.” This is a common invitation in yoga classes. However, sitting for an extended period is often awkward and uncomfortable. Just as each person’s body is different, each person’s ideal sitting posture is different. The quest for a comfortable seat is a great lesson in observation. Take some time over the next week to explore different postures. Sit in a chair, on the mat with legs crossed, on your knees, etc. Follow your breath and observe. What do you find comfortable? What is distracting? What props do you need? How do you feel? Take a look at the following for more ideas on sitting comfortably: Finding a Comfortable Seat, YJ Editors, Yoga Journal 5 Steps to Finding Ease in Sukhasana, Charlotte Bell, Yoga U To Fix That Pain in Your Back, You Might Have to Change the Way You Sit, Michaeleen Doucleff, NPR Breathe In yoga, we use the breath to focus and center our practice. Controlling the breath sends a message to your brain that you are safe and able to relax. The parasympathetic nervous system is activated, heart rate slows, and digestion is calmed. One of the many tools available to aid in this practice is mantra or breath prayer which involves the repetition of a word or phrase that is connected to inhaling and exhaling. Try one or more of these breath prayers (or use another of your own choosing) with your practice this week, saying in your mind the first part of the prayer on your inhale and the second on your exhale: Thanks / be I am / grateful Give / thanks Practice You can create a sustainable home yoga practice by focusing on doing what you love—what makes your feel good, what helps center you. Keep it simple and make it special by having a set place to practice and gathering the props you need for practice. Everyone can benefit from the use of props in practice, regardless of experience. Props offer access to greater space, freedom and stability. Consider investing in the following props as you continue to build your practice: mat, blocks, strap, bolster, blanket, tennis ball, eye pillow, sandbag, meditation cushion. You Yoga Journal and Yoga International offer many creative uses of props. “Acknowledging the good that you already have in your life is the foundation of all abundance.” Eckhart Tolle MEB Confiteor V. Patrick Ellis mixed media assemblage lumber/nails/house paint 2018 I confess to almighty God and to you, my brothers and sisters, that I have sinned through my own fault, in my thoughts and in my words, in what I have done and in what I have failed to do. I ask blessed Mary ever-Virgin, all the Angels and Saints, and you, my brothers and sisters, to pray for me to the Lord our God. The Sin of Omission

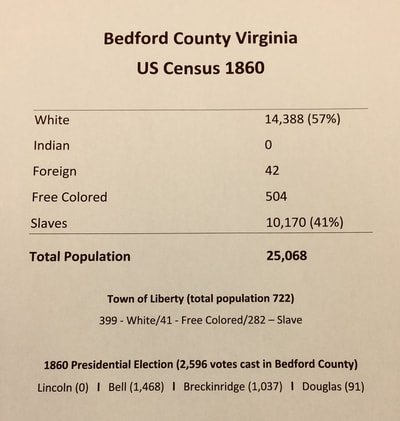

I have always loved that every Roman Catholic mass starts with a prayer of confession (Confiteor) and the collective admission of our deep and ongoing human brokenness. Before true communion with one another is possible, we must first confess that we have broken bonds with our god and with each other in our thoughts, in our words, in our actions … and what we failed to do (sin of omission). It is a transformative and humbling experience to say these words out loud … and in a public place. Sin is not just an offence against god. Our individual and collective brokenness has the power to wound our community and our world, our sin must be acknowledged before we can heal or be healed. As an adult person of faith, I have come to understand the true depth and power of this weekly prayer as a flood of new offences filled my mind with each recitation. Thoughts, words and actions were always the easy ones to conjure up. But a sin of omission, what I failed to do, takes a lot more effort and reflectiveness. These sins eventually come to my mind as well, and they always seemed to be so much more insidious. The times when I was silent when I should have spoken-up. The times when I failed to act when I witnessed cruelty of injustice. The times when my conscious informed me of the truth of a situation and I chose to participate silently in a collective wrong. The times when I did not exert the energy to seek out information and chose to live uninformed. It is so easy to hide this brokenness because the only witness to these sins is ourselves. Flag Narratives I am a son of the deep south. I was born in Mississippi, and I was raised in Tennessee and Georgia. My dad’s people hail from the prairie on the Alabama and Mississippi border. My mom’s kin are from Arkansas. But a nostalgia for the confederacy has always baffled me, as it does so many white southerners. I grew up surrounded by memorials to the civil war … ancient battles that continue to leave a scar upon the land and the collective memory. Chickamauga, Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain were central landscapes of my childhood … as was the ever-present icon of the south … with and its complexity of regional pride, history and humiliation … the confederate battle flag. I have youthful memories of three narratives for how the flag was used and remembered. There were the civil war memorials that utilized the flags of both the union and the confederacy as place markers. The battlefields of my memory were places of reflection and education. They had an almost Zen-like quality as places set apart to learn and to ponder greater human virtues like valor, honor and courage. These flags simply aided in telling the story. The flags carved into these memorials did not make judgments, rally or proselytize for a cause. I also grew up with the flag as a shibboleth for segregation and white supremacy. The presence or display of the confederate battle flag often signaled loyalty to a cause … a faithful remnant that would somehow rise victorious in a second great awakening. Even in my formative years I recognized in these folks an underlying anxiety, anger and fear to keep out perceived threats. It always seemed to me that these folks were angry at something deeper and unspoken. This symbol felt more tribal … as if kin and clan needed to be protected. And finally, the flag was honored or displayed as an overarching symbol of southern tradition and heritage. The flag becomes a catch-all symbol for regional pride and for the truly great attributes of a largely white southern culture. Like the inscription on Bedford’s civil war memorial the southern cause is framed in a language of valor; Their history is its brightest page, exhibiting the highest qualities of patriotism, courage, fortitude and virtue. This stone is erected to keep fresh in memory the noble deeds of these devoted sons. An Epic Footnote All these narratives about the confederate flag fall short. They inadequately convey the complexity of the civil war and too often intentionally omit the multifaceted narratives of race, economics and faith in this great American tragedy. The lasting scars that the confederate idea would inflict on the collective consciousness is born from a sin of omission … what we have failed to do … the stories we have failed to tell … the relationships we have failed to mend. In a recent interview with Anderson Cooper, the University of Richmond historian Julian Hayter was has asked if he thought the confederate monuments should come down. He said no … but added that they needed an epic footnote because they tell a very insufficient story of the war and its aftermath. Hayter suggests our energy should be put toward imagining ways to make visible the largely omitted stories of nearly half of the south’s population and place new memorials next to existing ones. He holds that the juxtaposition between the memorials and the omitted narratives and can make a compelling conversation and possibly healing. “Confiteor” is my attempt to visualize our collective sin of omission. I sought to ascribe a lens though which the confederate battle flag might have been be seen, understood and interpreted. All art (like politics) is essentially local. In 1860, enslaved people accounted for 41% of the population in Bedford County … 10,170 human beings were the property of other Bedford residents. I found that number as an epic local footnote and wanted to find some way to put it in a visual language. The confederate battle flag and 10,170 nails seemed the logical juxtaposition. Nails join two materials together, and in the joining together there is an intentionality of both will and force. The message is not in the flag or the nails, but rather the conversation between the two. Coda The other thing I like about the weekly recitation of the Confiteor was the understanding that reconciliation and forgiveness requires two things … god’s grace as well as the mercy and help of our brothers and sisters. Reconciliation is possible only when we understand our connectedness to god, each other and our world. This installation is a meditation on the ancient folk tale of the three young men in the fiery furnace found in the Book of Daniel. A universal story of a people conquered by a foreign power and forced into exile and bondage in a strange and hostile new world. Taken as trophies because of their wisdom and unblemished beauty, Hananiah, Mishael and Azariah are given the new names of Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego to rob them of their cultural identity and reflect the greatness of their new foreign king and his gods. Separated from their families, their land, and the practices of their faith, these men become architypes for the transformative power of truth and a faithfulness to tradition in the midst of exile, oppression and injustice. Defeated but not broken, these three young men, along with their companion Daniel (renamed Belteshazzar), remain faithful to their god through their cultural touchstones of food, prayer and worship. For a time, because of their skills, cleverness and wisdom, these companions find ways to win the heart and mind of the king and are appointed to prominent positions in the kingdom. But when the king builds a great golden statue to himself and demands that all his subjects must fall down and worship it or be thrown into furnace of blazing fire, the exiles are forced to make a public stand and declaration of their faith in their god. The satraps, prefects, governors and counselors, treasurers, justices, magistrates and all the officials of the provinces seize upon the king’s decree as a way to finally trap and break the will of these young men. Brought before the enraged king, these companions make their stand saying: “O king we have no need to present a defense to you in this matter. If our god whom we serve is able to deliver us from the furnace of blazing fire and out of your hand, O king, let him deliver us. But if not, be it know to you, O king, that we will not serve your gods and we will not worship the golden statue that you have set up.” While we know the rest of the story and the three young men come out of the furnace of fire unscathed, the Book of Daniel is not a “we all live happily for ever after” folktale. The story celebrates the transformative power of truth and faithfulness to tradition amidst the ongoing history of tyrants, those who perpetuate injustice and those who deny others their full humanity and freedom. The technique I utilized for this installation is an assemblage of found and recycled objects. The style is in the aesthetic, as well as form, of narrative totem poles found in past and present primal religious cultures around the world. My attraction to the art and aesthetics of primal religious traditions manifold.

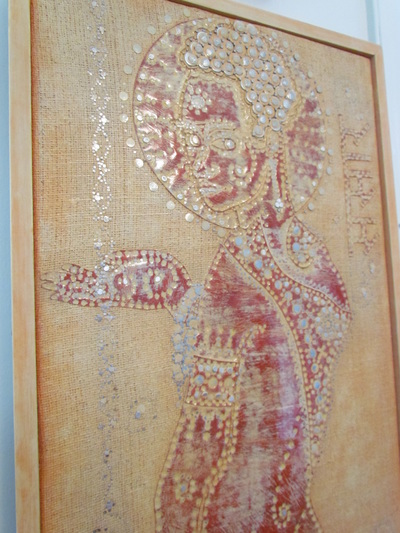

Our friend and mentor Bobbie Crow died in early March. In tribute, the following are some reflections on her influence on our work and ministry along with some of her artwork and some of our own art inspired by her. "You Brood of Vipers" Bobbie Brooks Crow awakened in me the desire to see and to seek the spiritual in art. This assemblage pays homage to a friend and art mentor and a small pen and ink sketch she did in church on the first Sunday in Advent many decades ago. Bobbie sings in the choir of Grace Episcopal Church in Chattanooga TN. It is her habit to bring a small sketchbook to capture images from the scripture stories or the pastoral message that catches her imagination. On this particular Sunday in late November the apocalyptic words of a prophet crying in the wilderness caught her attention. You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come? Even now the ax is lying at the root of the trees; every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. Bobbie’s image of the prophet John the Baptist juxtaposes him next to a fruit bearing tree. John’s words are not just angry rhetoric … he is ready for the great pruning. The world has gone so terribly wrong and only a direct intervention from God can save possibly save humanity. John announces a world on the threshold of transformation. The red gash across his neck hints to the cost of his prophetic message and his discipleship. While John’s words were aimed directly at his brother Jews and their empty words and actions, his message resonates in all ages in which God’s gift and promises are not made available to all in God’s creation … to act justly and walk humbly with God. For Bobbie, the tree is Christmas tree and a reminder of humanity’s perversion of God’s great act of love (bad fruit as witnessed in commercialism of the incarnation and the Nativity event), but the tree is also a sign of hope that points toward God’s original intent for creation (good fruit as witnessed in the right relationships embodied in the story of Garden of Eden and the Tree of Life). The technique I utilized for this homage is an assemblage of found and recycled objects. The style is in the aesthetic, as well as form, of narrative totem poles found in many primal religious cultures around the world. I these traditions, the form is simplified to only the elements critical to the ethical narrative … in this case eyes to see injustice, a mouth to speak truth and a hand to carry out God’s work within creation. -VPE The Road to Emmaus Karen Armstrong begins her book “Twelve Steps to a Compassionate Life” by identifying the human struggle in which we must constantly seek a balance between the “old brain” or “reptile brain” that we carry with us from our primal ancestors and the “mature” brain into which we have evolved as Homo sapiens. The latter is capable of compassion such that the Buddha identified in the Four Immeasurables – maitri (loving kindness), karuna (compassion), mudita (sympathetic joy), and upkesha (even-mindedness). Conversely, the former is driven by what Armstrong refers to as the Four Fs – “feeding, fighting, fleeing – and for want of a more basic word – reproduction.” Armstrong’s premise is that compassion is like a muscle and must be exercised to help it grow stronger. Compassion comes when we recognize the sacred in ourselves and in others. Armstrong highlights three biblical stories in which the characters come to such a recognition – Sarah and Abraham’s encounter with the strangers at the Oak of Mamre, Jesus appearing to the two on the road to Emmaus, and Jacob wrestling with the angel. Each story revolves around the themes of hospitality, unknowing/knowing, and recognizing the divine in others. In particular, the climax of Emmaus story occurs as the disciples offer hospitality and a shared meal with the stranger. The unknowing becomes knowing through acts of compassion. Bobbie Crow's Road to Emmaus sketch, which hangs in my studio, serves as a reminder of this truth and inspired my Road to Emmaus mosaic. When he was at the table with them, he took bread, gave thanks, broke it and began to give it to them. Then their eyes were opened and they recognized him, and he disappeared from their sight. They asked each other, “Were not our hearts burning within us while he talked with us on the road and opened the Scriptures to us?” Moving forward toward a compassionate life, we are required to direct compassion toward our fellow human beings. Armstrong recommends a Metta mediation using the Four Immeasurables – directing each of the four toward others. Using the example of Greek tragedies, she also makes a powerful argument for the importance of art in developing compassion. She writes, “Compassion and abandonment of ego are both essential to art…Art calls us to recognize our pain and aspirations and to open our minds to others. Art helps us…to realize we are not alone; everybody else is suffering too.”

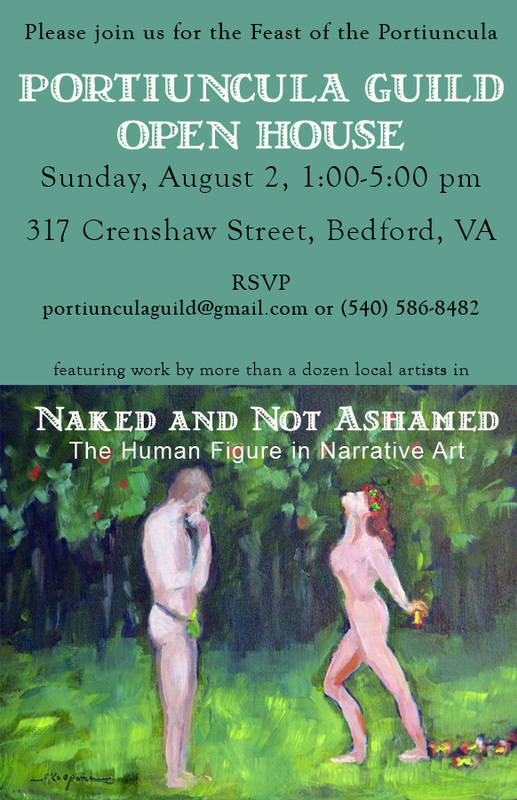

Bobbie Crows obituary refers to her using the title "Collaborative Artist." Indeed for Bobbie, the art making process was about abandoning ego and welcoming strangers. She was known for orchestrating monumental public art pieces created in part by a community of people. Spreading a large canvas on the ground, she would create gesture outlines using paint squeezed from a plastic bottle. Then armed with buckets of paint and a brush duct-taped to the end of a broom stick she would invite passersby to add color to the canvas. Handing the brush to folks she would say, "Here. Make your mark." -MEB We were honored to open the Portiuncula Guild up as part of the Bedford Council of Garden Clubs Home Tour in December 2015. Here are some pics and excerpts from a handout we prepared: Through the work of the Portiuncula Guild, Mitchell Bond and Patrick Ellis seek to build relationships and conversations between artists working at the intersection of faith, spirituality and creative expression, as well to promote their work and vision to a wideraudience. Four times each year the home owners host an open house gathering centered on a community art exhibition. The core themes for these art exhibitions are derived from the narratives of the yearly feasts and commemorations of the Christian liturgical year. Specific themes within these narratives are chosen to reflect universal experiences which peoples of all faiths (or of no faith) share. The works of art in the current exhibition in the gallery are taken directly from the collection of the home owners and were arranged to reflect the theme of “Mystery of the Incarnation”. The Advent and Christmas seasons hold a special place in the heart of Franciscan life in that tradition suggests that St. Francis and his early band of followers created the first Christmas crèche. But this season is more than just the baby in the manger. This is an epic narrative of a broken world, God’s love for creation, and the rich cast of characters who had the faith to work with their God in a plan to redeem the world. Like most of the art found throughout this home, the artists in this exhibition interpret the meaning and depth of the stories of faith much like a pastor who preaches on, teaches about or interprets the biblical stories for a community of faith. These artists come from a variety of faith backgrounds, but all share a desire to utilize the creative imagination to explore the narratives and struggles common within all human life and culture.

Goose Creek Studio was pleased to partner this year with a dozen or so local businesses, community organizations and the Town of Bedford to bring renewed life to our beleaguered farmers market. Under the leadership of a management team and our new market manager, the growth of and changes to the market have been no less than miraculous. Good things happen when the community comes together, and as a result, the market has become a place of community pride and witness to the entrepreneurial spirit of local area farmers and artisans. But this is not a reflection on the local farmers market, but an exploration on the transformative power of art. Early in the market season, we asked local photographer Robert Miller to shoot images of vendors and shoppers, as well as the rich variety of produce and products that would be for sale. We commissioned Miller for the task because we wanted more than just a visual record. We wanted him to capture the new life and the renewed energy emerging from the market and this collaborative community spirit. We had long admired the work Miller has done documenting events at the Sedalia Center, Bower Center for the Arts, 2nd Fridays, Centerfest and of course, our own events at Goose Creek Studio. In his engagement with this community over the past several years, Miller has revealed the transformative power of the photographic image to build community identity. Miller’s work creates a very different kind of art exhibition and a fresh way of seeing. His work is not stagnant or isolated to the obscurity of the white walls of the art gallery, but is a living art found regularly in the local newspapers and his consistent social media posts. He has a talent for capturing the vitality and creative spirit of an event and getting those images back out into the wider community, and thus, his art engages us in ways traditional art exhibitions rarely do. Gallery shows are often quiet and somber affairs as individuals silently contemplate a picture on the wall. Miller’s social media posts of events he has photographed provide a very different way of encountering the visual image. Miller creates a community conversation that is more dialogue and discovery than aesthetic contemplation. The community claims ownership of his work as they see themselves, their friends and the vitality of their community in his images. In many ways it hearkens back to an older understanding of the artists/artisan as a servant of the community’s ritual moments. Miller’s photographs are not just documentary, they are an art form. He intentionally manipulates and filters the events that he shoots. A recognizable hallmark is his use of very bright and saturated colors. For Miller, the art making process only begins with what he sees through the lens and the click of the shutter. The power of his art is not just in his ability to choose a moment in time, compose a balance composition or even master the mechanics of his camera. The art making process really happens after Miller gets home and starts to process his images and weaves his shots into a more all-inclusive storytelling. The processing of his images post event becomes a critical component for making the image speak beyond the particulars of a moment in time. Great art is never solely about the artistic skills of an individual. Rather, great art captures and communicates something important about a particular time or people. And in that desire to communicate, great art seeks truth and is often willing to bend the visual particulars to seize the narrative thread. For Miller to capture the essence of an event, he needs to literally change or embellish what the camera has captured. We all do the same thing in our own story telling and remembering. In fact, manipulation, embellishment or hyperbole are often critical ways to emphasize the role of an individual or the narrative of a story. “My grandma made the best cookies in the world.” The truth of that statement is not in the verifiable accuracy of the facts or grandma’s culinary skills, rather, the statement communicates the quality of a relationship. The true superiority of grandma’s cookies can only be understood in the depth on a relationship to her, and to communicate the depth of that relationship requires creative emphasis. If we focus only on the detail, we can miss the essence and the transformative power of a story. Great art often communicates in much the same way. In the same way Miller manipulates the image digitally to capture the truth in his seeing. Digital manipulation, filters and rich saturated colors are his tools for storytelling by serving as a way to concentrate on the narrative action. Miller understands the relational complexities of any event and works to capture a rich variety of vignettes. A single image can never hold the weight of an entire community gathering. And since the camera can only capture a momentary vignette within the rich complexities of ongoing actions, objects and relationships, Miller’s documentation of an event must be viewed through holding the multiple images together as a single thread. When photographing a public event, Miller focuses his camera on people in relationship to one another, in relationship to their career or trade, or in the expression of their individuality or personality. He weaves each vignette he captures into the larger mood of the day. A series of ordinary moments that take on more universal qualities and a more complete story of who and what this community is or seeks to become. In an arts community with an almost obsessive preoccupation with the more established forms for celebrating merit is artistic achievement … the gallery exhibition, sales or awards, Miller is forging a new (and maybe healthier) way for art to engage the community and for the community to encounter the transformative power of art.

The message Miller communicates is not focused on an individual or object, but rather in the space that is created between the individual and object. Miller’s images communicate a quality of a relationship. His art is about shaping community identity by crafting images of who we are and what we do. - MEB & VPE |

Archives

October 2022

Categories

All

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed