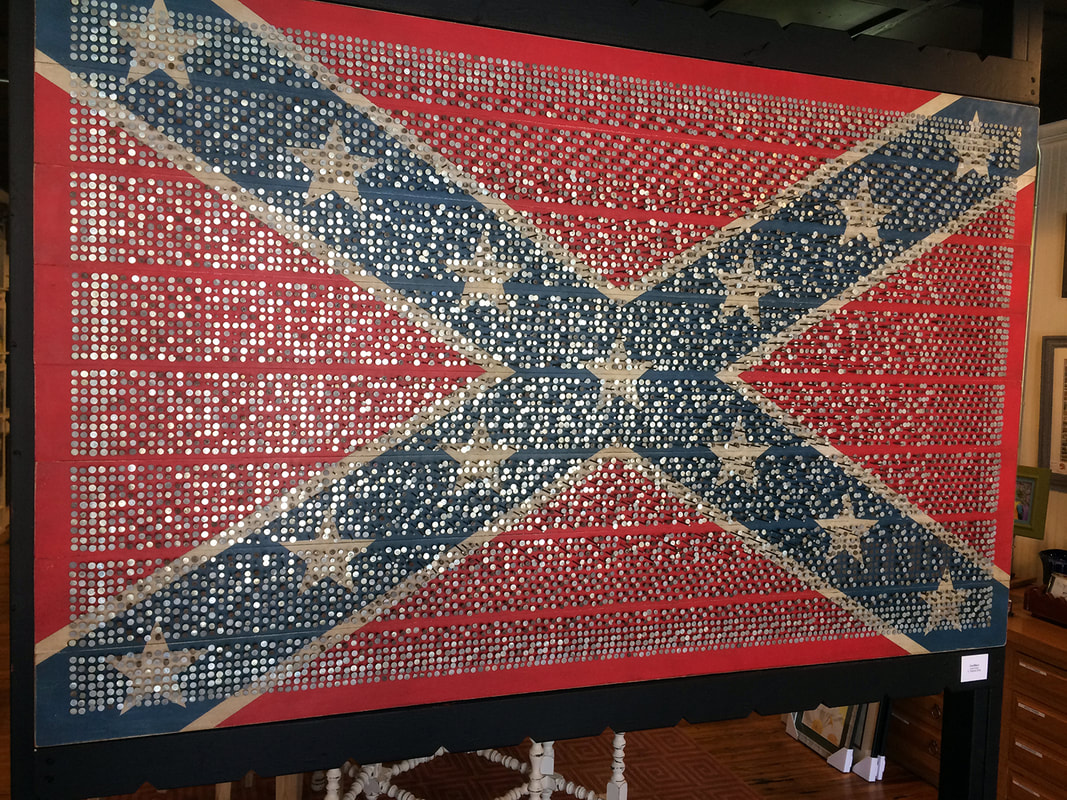

V. Patrick Ellis

mixed media assemblage

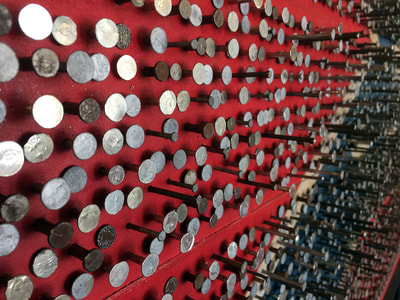

lumber/nails/house paint

2018

I confess to almighty God

and to you, my brothers and sisters,

that I have sinned through my own fault,

in my thoughts and in my words,

in what I have done

and in what I have failed to do.

I ask blessed Mary ever-Virgin,

all the Angels and Saints,

and you, my brothers and sisters,

to pray for me to the Lord our God.

I have always loved that every Roman Catholic mass starts with a prayer of confession (Confiteor) and the collective admission of our deep and ongoing human brokenness. Before true communion with one another is possible, we must first confess that we have broken bonds with our god and with each other in our thoughts, in our words, in our actions … and what we failed to do (sin of omission). It is a transformative and humbling experience to say these words out loud … and in a public place. Sin is not just an offence against god. Our individual and collective brokenness has the power to wound our community and our world, our sin must be acknowledged before we can heal or be healed.

As an adult person of faith, I have come to understand the true depth and power of this weekly prayer as a flood of new offences filled my mind with each recitation. Thoughts, words and actions were always the easy ones to conjure up. But a sin of omission, what I failed to do, takes a lot more effort and reflectiveness. These sins eventually come to my mind as well, and they always seemed to be so much more insidious.

The times when I was silent when I should have spoken-up. The times when I failed to act when I witnessed cruelty of injustice. The times when my conscious informed me of the truth of a situation and I chose to participate silently in a collective wrong. The times when I did not exert the energy to seek out information and chose to live uninformed. It is so easy to hide this brokenness because the only witness to these sins is ourselves.

Flag Narratives

I am a son of the deep south. I was born in Mississippi, and I was raised in Tennessee and Georgia. My dad’s people hail from the prairie on the Alabama and Mississippi border. My mom’s kin are from Arkansas. But a nostalgia for the confederacy has always baffled me, as it does so many white southerners.

I grew up surrounded by memorials to the civil war … ancient battles that continue to leave a scar upon the land and the collective memory. Chickamauga, Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain were central landscapes of my childhood … as was the ever-present icon of the south … with and its complexity of regional pride, history and humiliation … the confederate battle flag.

I have youthful memories of three narratives for how the flag was used and remembered.

There were the civil war memorials that utilized the flags of both the union and the confederacy as place markers. The battlefields of my memory were places of reflection and education. They had an almost Zen-like quality as places set apart to learn and to ponder greater human virtues like valor, honor and courage. These flags simply aided in telling the story. The flags carved into these memorials did not make judgments, rally or proselytize for a cause.

I also grew up with the flag as a shibboleth for segregation and white supremacy. The presence or display of the confederate battle flag often signaled loyalty to a cause … a faithful remnant that would somehow rise victorious in a second great awakening. Even in my formative years I recognized in these folks an underlying anxiety, anger and fear to keep out perceived threats. It always seemed to me that these folks were angry at something deeper and unspoken. This symbol felt more tribal … as if kin and clan needed to be protected.

And finally, the flag was honored or displayed as an overarching symbol of southern tradition and heritage. The flag becomes a catch-all symbol for regional pride and for the truly great attributes of a largely white southern culture. Like the inscription on Bedford’s civil war memorial the southern cause is framed in a language of valor; Their history is its brightest page, exhibiting the highest qualities of patriotism, courage, fortitude and virtue. This stone is erected to keep fresh in memory the noble deeds of these devoted sons.

An Epic Footnote

All these narratives about the confederate flag fall short. They inadequately convey the complexity of the civil war and too often intentionally omit the multifaceted narratives of race, economics and faith in this great American tragedy. The lasting scars that the confederate idea would inflict on the collective consciousness is born from a sin of omission … what we have failed to do … the stories we have failed to tell … the relationships we have failed to mend.

In a recent interview with Anderson Cooper, the University of Richmond historian Julian Hayter was has asked if he thought the confederate monuments should come down. He said no … but added that they needed an epic footnote because they tell a very insufficient story of the war and its aftermath. Hayter suggests our energy should be put toward imagining ways to make visible the largely omitted stories of nearly half of the south’s population and place new memorials next to existing ones. He holds that the juxtaposition between the memorials and the omitted narratives and can make a compelling conversation and possibly healing.

“Confiteor” is my attempt to visualize our collective sin of omission. I sought to ascribe a lens though which the confederate battle flag might have been be seen, understood and interpreted.

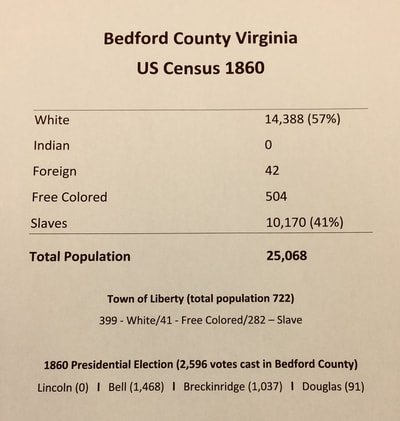

All art (like politics) is essentially local. In 1860, enslaved people accounted for 41% of the population in Bedford County … 10,170 human beings were the property of other Bedford residents. I found that number as an epic local footnote and wanted to find some way to put it in a visual language. The confederate battle flag and 10,170 nails seemed the logical juxtaposition. Nails join two materials together, and in the joining together there is an intentionality of both will and force. The message is not in the flag or the nails, but rather the conversation between the two.

Coda

The other thing I like about the weekly recitation of the Confiteor was the understanding that reconciliation and forgiveness requires two things … god’s grace as well as the mercy and help of our brothers and sisters. Reconciliation is possible only when we understand our connectedness to god, each other and our world.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed